ACTION

RESPOND TO ISSUES YOU CARE ABOUT,

EXTEND YOUR DEFINITION OF CIVIC ACTION

IN THE DIGITAL AGE

QUESTION Three:

Is online activism “slacktivism” or

just a different way to take action?

How can it be risky?

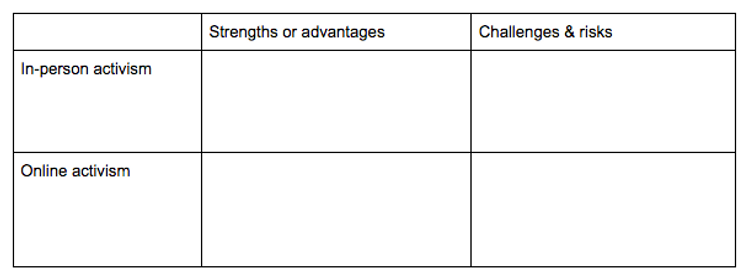

Activity: In-Person Activism vs. Online Activism

(45-60 minutes)

Have your students read sections from the 3 article excerpts included below and explore the strengths and challenges of in-person versus online activism using the following graphic organizer to document the authors’ claims. (Feel free to include any evidence from the Eyes on the Prize or Digital Media & Struggles for Justice videos, too.)

“The Revolution will not be Tweeted.”

The term “slacktivism” has been used to suggest that online actions ranging from blogging or tweeting about an issue to signing an e-petition are thin or less consequential than higher burden activities such as sit-ins, rallies, and other forms of offline protest. In this article, Malcolm Gladwell agrees with this perspective and argues that “the revolution will not be tweeted.”

Have your students read the following excerpt from Gladwell’s article and take notes on the graphic organizer:

“Greensboro in the early nineteen-sixties was the kind of place where racial insubordination was routinely met with violence. The four students who first sat down at the lunch counter were terrified. “I suppose if anyone had come up behind me and yelled ‘Boo,’ I think I would have fallen off my seat,” one of them said later. On the first day, the store manager notified the police chief, who immediately sent two officers to the store. On the third day, a gang of white toughs showed up at the lunch counter and stood ostentatiously behind the protesters, ominously muttering epithets such as “burr-head nigger.” A local Ku Klux Klan leader made an appearance. On Saturday, as tensions grew, someone called in a bomb threat, and the entire store had to be evacuated….

So one crucial fact about the four freshmen at the Greensboro lunch counter—David Richmond, Franklin McCain, Ezell Blair, and Joseph McNeil—was their relationship with one another. McNeil was a roommate of Blair’s in A. & T.’s Scott Hall dormitory. Richmond roomed with McCain one floor up, and Blair, Richmond, and McCain had all gone to Dudley High School. The four would smuggle beer into the dorm and talk late into the night in Blair and McNeil’s room. They would all have remembered the murder of Emmett Till in 1955, the Montgomery bus boycott that same year, and the showdown in Little Rock in 1957. It was McNeil who brought up the idea of a sit-in at Woolworth’s. They’d discussed it for nearly a month. Then McNeil came into the dorm room and asked the others if they were ready. There was a pause, and McCain said, in a way that works only with people who talk late into the night with one another, “Are you guys chicken or not?” Ezell Blair worked up the courage the next day to ask for a cup of coffee because he was flanked by his roommate and two good friends from high school.

The kind of activism associated with social media isn’t like this at all. The platforms of social media are built around weak ties. Twitter is a way of following (or being followed by) people you may never have met. Facebook is a tool for efficiently managing your acquaintances, for keeping up with the people you would not otherwise be able to stay in touch with. That’s why you can have a thousand “friends” on Facebook, as you never could in real life.

This is in many ways a wonderful thing. There is strength in weak ties, as the sociologist Mark Granovetter has observed. Our acquaintances—not our friends—are our greatest source of new ideas and information. The Internet lets us exploit the power of these kinds of distant connections with marvellous efficiency. It’s terrific at the diffusion of innovation, interdisciplinary collaboration, seamlessly matching up buyers and sellers, and the logistical functions of the dating world. But weak ties seldom lead to high-risk activism.”

You may also choose to have your students read the full article, which can be accessed here: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2010/10/04/small-change-malcolm-gladwell

“Slacktivism for Everyone!”

Other people argue that digital media have ‘changed the game’ of civic action. Taking action can be easier yet still lead to impact.

In the article, “Slacktivism for Everyone: How Keyboard Activism is Affecting Social Movements,” Jennifer Earl explores how online activism has helped people who may otherwise not engage in civic issues, take a crucial first step towards participation.

Have your students read the following excerpt from Earl’s article:

“In 2013, an online petition persuaded a national organization representing high school coaches to develop materials to educate coaches about sexual assault and how they could help reduce assaults by their athletes. Online petitions have changed decisions by major corporations (ask Bank of America about its debit card fees) and affected decisions on policies as diverse as those related to survivors of sexual assault and local photography permitting requirements. Organizing and participating in these campaigns has also been personally meaningful to many.

But, a nostalgia for 1960s activism leads many to assume that “real” protest only happens on the street. Critics assume that classic social movement tactics such as rallies and demonstrations represent the only effective model for collectively pressing for change. Putting your body on the line and doing that collectively for decades is viewed as the only way “people power” works. Engaging online in “slacktivism” is a waste, making what cultural commentator Malcolm Gladwell has called “small change.”...

Critics often worry that valuing flash activism will “water down” the meaning of activism. But that misses the point and is counterproductive. The goal of activism is social change, not nostalgia or activism for activism’s sake. Most people who participate in flash activism would not have done more – rather, they would have done nothing at all.”

You may also choose to have your students read the full article, which can be accessed here:

Caution, Risks Ahead: Deport Nancy M. Campaign

As an activist involved the immigration reform effort in the U.S., Nancy M. (name shortened to provide anonymity) learned first-hand that online activism can have real world, and potentially dangerous, repercussions. In carrying out media outreach activities to advocate passage of the DREAM Act, Nancy M. was targeted for deportation by an anti-immigrant group. The group publicized her whereabouts and her identity. They also invested in t-shirts and other items advocating for her deportation.

Here is an excerpt that you may choose to share with your students:

“On May 20, 2010, nine brave students sat down in the middle of Wilshire Boulevard in front of the West Los Angeles Federal Building to advocate for passage of the DREAM Act. The Wilshire Nine action took place three days after DREAM Act students staged a sit-in at Senator McCain’s office in Arizona. In Los Angeles, immigrant youth came together to take part in a similar non-violent direct action. Direct action disrupts “business as usual” but most importantly, it is an act of sacrifice by individuals who are willing to put themselves at risk in order to push for the greater good….

I was stationed with my laptop computer and cell phone a few blocks away at a coffee shop, conducting media outreach for the action. The coffee shop was our makeshift office, and I sent out press releases with updates and took calls from many reporters. I was identified as the media spokesperson on the press release, and my cell phone number was listed….

As I was conducting an interview for an international cable news show, my phone began to ring repeatedly. I answered a few calls and was attacked and insulted. One caller told me, “You need to understand that illegal is illegal,” whereas another voiced that “illegals like you need to be deported back to Mexico.” I soon learned that a national campaign had been started by the conservative AM radio talk show to call for my deportation.”

You may also choose to have your students read the full article, which can be accessed here:

https://www.alternet.org/immigration/my-activism-resulted-right-wing-campaign-my-deportation

Click here to download this exercise as a PDF.

Class Activity

As a class or in small groups, ask students to discuss the ideas they drew from the articles and wrote on their graphic organizer. Then ask students to discuss the following broad questions:

-

What strategies might one use to navigate the challenges and risks of offline and online activism?

-

How will the strategies you came up with help address the challenges and risks?

-

What concerns or worries do you still have?